2. Steps in Planning & Implementing a Service-Learning Course

Reiter

Course of Action

We have already talked about what Service-Learning is, its core elements, specific roles and special forms.

But how do you organize a Service-Learning course? This part serves as guide on how to conceptualize, implement and assess a Service-Learning course. Our road map guides you through the different steps for planning and implementing a S-L idea, while our info boxes provide tips and issues to consider.

By the end of this chapter, you will have a basic understanding of each necessary step and the respective time frame.

You can find the whole road map on our website: https://uni-tuebingen.de/en/198853

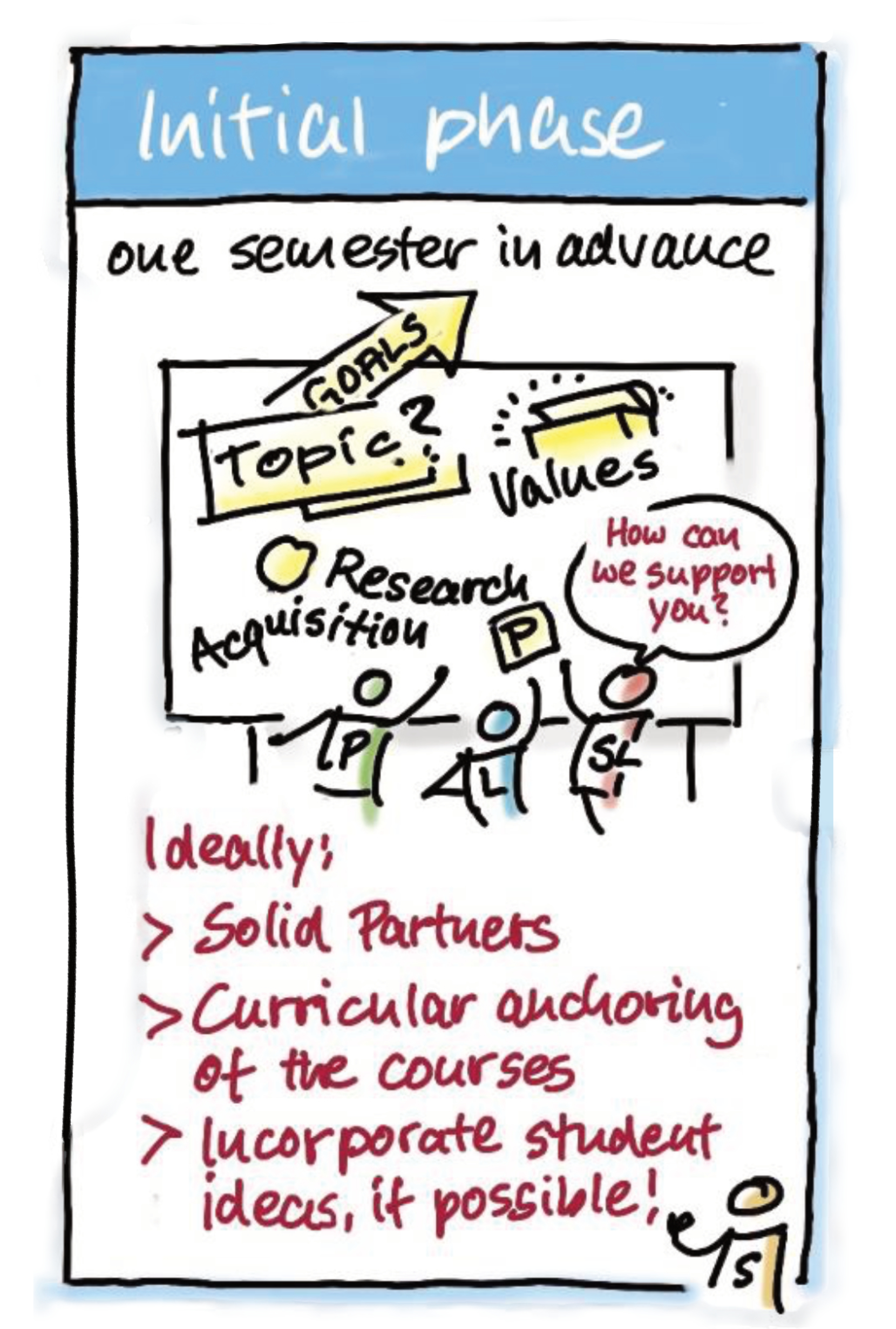

During the initial phase, the lecturer and the community partner (and the S-L team) form a partnership, after having identified a community need that calls for the expertise and commitment of the lecturer and students to solve it. The initial idea may come from each of the actors, including students.

Certain questions should be addressed or kept in mind, like:

- Which social need will be faced?

- What are the learning objectives?

- Which type of service will the students provide?

Time Frame

As with every course creation, adequate time should be appointed to this phase.

The preparation should begin at least one semester before the course is offered to the students.

Social Need

In order to qualify as a Service-Learning course, you need to detect social needs that are relevant to the community and determine which ones could be attended to by the students. As a lecturer, you can approach this step based on your academic expertise and, subsequently, discuss your suggestions with a suitable community partner. Alternatively, you can also reach out to community partners and jointly brainstorm how to connect your research focus with the community partner's need.

We suggest trying to link the social need and, hence, also the service with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which is a collection of 17 interlinked global goals designed to achieve a better and more sustainable future.

Connection with CIVIS

If you are participating in CIVIS, a European Civic University formed by the alliance of 11 leading research higher education institutions across Europe, it might also be of interest to you to relate the social need to the 5 CIVIS themes:

- Health

- Cities, territories and mobilities

- Digital and Technological transformation

- Climate, environment and energy

- Society, culture, heritage

Collaboration with community partners

The partners are a key aspect and a main actor of the service, so it is very important to select them cautiously and collaborate with them on an equal footing.

For initiating the collaboration, you may contact partners you have already worked with or map (non-profit) organizations and public administrations dealing with the needs that need to be addressed. Usually, non-profit entities, entrepreneurs, public administrations, educational centers and cultural organizations are preferred, but always pay close attention to their values and goals in order to ascertain that both of you are on the same page.

Since a successful cooperation can only be built on trust, reliability and transparency, plenty of time should be allowed to get to know each other and, if possible, to exchange visits. In order to prevent misunderstandings due to a clash of expectations, it is also wise to agree on common goals, responsibilities and arrangements with everyone involved at the start of the project. A way to simplify the cooperation between you and a partner is to try to create a solid and sustainable collaboration. After clear communication with the partner about the goals and the expectations to have a written agreement e.g., in the form of a mutually signed collaboration agreement between the higher education institution and the partner can be helpful.

While planning the course, keep in mind that on your part, it is important to match learning objectives with social needs.

During this phase, it is also important to develop the content together with the community partners to enable a reciprocal partnership. In this way, everyone involved in the course works together on an equal footing. This means that they perceive themselves as equal partners and are open to learning from each other.

Throughout the conceptualization and the implementation of the course, everyone should be aware that outcomes may differ from the community partners’ initially desired goals. In this case, it should be jointly discussed how to deal with divergent developments. As a lecturer, you should be in close contact with your partners in the project.

In the ensuing Planning Phase, everyone involved needs to identify precisely the desired learning and service elements, while maintaining a balance between the academic learning objectives and project goals. Doing so appreciatively and on an equal footing will foster the self-perception as equal partners and the willingness to learn from one another. Therefore, it is good to clarify mutual expectations, communicate any difficulties in a timely manner, discuss potential reflection opportunities and – overall – have a realistic expectation of what can be achieved over the course of the allocated time (e.g., in one or two semesters).

Depending on the project, students might not only directly contact the community partner but also its target groups. Since the students sometimes interact with people from other professions or fields of study and other social backgrounds, including potentially traumatized people and in different institutional hierarchies, they should receive suitable preparation for this e.g., workshops or appropriate reading.

This interaction as well as extra elements of the service should be considered when calculating the associated credit points (1 credit point equals 30 hours of student workload). In regards to your workload (Deputat), specific consultation hours are relevant in addition to the plenary sessions. Here, above all, communication with the students regarding any hardships or questions can be facilitated. If possible, a student with previous experience in S-L can serve as a tutor. In this way, both you and your students can have an intermediate mean of communication, while providing a great opportunity for the student/tutor to gain experience in teaching.

Involving the students

A Service-Learning course should be transparent and consider all actors as equally engaged, including the students. A way to motivate the students and encourage them to work independently is to allow them to be involved in the project as far as possible and in all phases of the project from the beginning. If it is not possible for the students to be involved in the concept stage, then they should at least be offered plenty of leeway to develop their own ideas in relation to a topic.

- When planning e-Service-Learning courses, you can consider employing activating online tools or combining asynchronous with synchronous parts.

- Keep in mind that your students are creative, too. So, do not shy away from involving them in finding the best way to work in a motivated fashion!

As mentioned in the previous chapter, students may derive from different disciplines and, thus, carry a diverse repertoire of skillsets. Inversigating or acknowledging this diversity will only benefit the achievability of the course. Furthermore, students sometimes interact with people from other professions or fields of study, other social backgrounds, including potentially traumatized people, and in different institutional hierarchies. In order to deal with all possible challenges, they should receive suitable preparation for this. For example, on communication courses or appropriate reading.

To investigate and identify the missing skills, you can use the following questions:

- What tasks are related to the service?

- What requirements are needed to perform the tasks?

- Do students need specific training before the service starts?

Constructive Alignment

Please note that in S-L, the academic performance of students is assessed, not the civic engagement throughout the service element. Constructive Alignment is a teaching model, which can help you when planning courses by coordinating learning objectives with teaching and learning methods, as well as the final assessment (Biggs, 1996).

For example, if the learning objective for the students is to be able to write well-informed and structured blog articles, teaching them numerous facts about writing alone will not suffice. Instead, they will need to practice writing and researching facts.

Please find an OER introduction to Constructive Alignment by Rafael Klöber (University of Heidelberg) in our Methods & Tools box.

Assessment

In the end, the academic performance of the students (learning) is assessed, not their civic engagement (service). The evaluation criteria should be transparent. By disclosing the learning objectives and aligning them with the teaching and learning methods and the examination format, students are able to learn deeply - as suggested in constructive alignment.

Their cognitive performance should be measured based on the knowledge and the new competencies gained e.g., reasoning, thinking, remembering, problem solving or decision making. The indicators used for measuring their performance should be communicated to the students early on. Examples of assessment questions and tasks or a simulation of the assessment situation allows students to perform better at their final exams.

- an essay or another written form or assignment

- an e-portfolio, where they document their learning process,

- a reflection essay,

- a group assessment in the form of an oral presentation etc.

The assessment can be either result-oriented (summative) which occurs only at the end of the semester or process-oriented (formative), which is spread over the semester. For example, the assessment can be spread into a presentation (25%), a field research report (25%) and a final presentation (50%). Alternatively, the students could create a blog concept (30%), their own blog posts (35%) and a written essay (35%).

The provision of the evaluation criteria can be presented in the form of a grading rubric. Apart from the course evaluation, there should be a reflection on the learning that was achieved and the results of the service. Potential future prospects can also be discussed with the students in case they want to stay involved in the project.

Furthermore, an evaluation with the community partner, as well as a self-evaluation of the lecturer(s) is highly recommended.

At the start of the semester, the implementation phase begins:

At a kick-off event, all participants become familiar with each other, the challenge ahead and organizational issues. Particularly in the first sessions, students should be helped to assess the achievability of goals realistically. This is also a suitable time for a first critical reflection on the suitability or unintended consequences of the service element (Crabtree, 2013). Any changes regarding the general goals should be made transparent.

The individual steps should also be documented regularly e.g., in the form of a portfolio, which can be used as a basis for a possible final report. In this phase, students will learn individually or in groups, work on assigned parts of the challenge and reflect on the transfer between the academic knowledge and their personal involvement in practice. For this, you and the community partner need to guide and coach students, while giving them plenty of leeway to develop ideas in relation to the topic.

Separate approaches regarding the independence of the students should be taken into account like the academic level of the students, BA or MA and the goal of the activity. Throughout this phase, you and the community partner should also stay in touch with one another to communicate difficulties as soon as possible.

At the end of the semester, the completion phase follows.

A common celebration of the achieved results can be realized, for example, by presenting them or handing them officially over to the community partner during the last meeting or during a (semi-) public event. During the latter, the joint achievements are celebrated and publicly accessible. It can also serve as a platform to raise attention for this innovative format and, thus, may motivate fellow faculty/department members to give Service-Learning a try. So, make sure to invite students and colleagues from your department or your faculty, as well as members of the civil society. A final reflection should be included during the last session.

The follow-up phase can then be used to assess students’ work, issue certificates of attendance, and add the final touch to the results. Finally, you can build on your experience and the established trust between you and the community partner in order to develop future S-L projects for the up-coming semesters.

Time Frame

Please allocate some time for refinements, since finalizing the course results often requires consultation with the community partners.

Well Worth the Effort

The aspects of Service-Learning activities dealt with here clearly show that this teaching and learning format requires a considerable degree of planning, coordination and flexibility from everyone involved. This effort pays off, however, because students experience how science can have a real impact and provide concrete solutions for social needs. This experience promotes understanding of the role of science in society and fosters the sense of social responsibility. The exchange of knowledge in Service-Learning activities benefits not only the civil society partners, but also students and lecturers.

We are constantly developing our materials. Therefore, we would be pleased if you could send us your feedback on your learning experience using this OER.

Please write to:

Charoula Fotiadou, charoula.fotiadou@uni-tuebingen.de

Nina Rösler, nina.roesler@uni-tuebingen.de

Do you need more methods and tools? Go to our Methods & Tools unit and find more information on constructive alignment, reflection tasks in class, research-based teaching and learning and quality criteria for Service-Learning!

This e-learning course uses the licences of CC-BY-SA (4.0).

BY: When using or otherwise citing the entire or parts of this e-learning course, you are required to give appropriate credit and provide a link to the licence. (Authors: Charoula Fotiadou and Nina Rösler).

SA: You may share (copy and redistribute) and adapt (remix, transform, and build upon) the content given in this course. You are required to indicate any changes you made.

More information can be found on the creativecommons website.